Time, as we understand it today, was not really invented but rather discovered, measured, and organized by humans to make sense of the natural world. From the very beginning, people noticed patterns in nature—the rising and setting of the sun, the changing phases of the moon, and the repeating seasons. These natural cycles were the first “clocks,” helping early societies keep track of days, months, and years.

The ancient Egyptians were among the first to create instruments to measure time more precisely. They used sundials, which cast shadows with the sun’s movement, to divide the day into smaller parts. At night, they relied on water clocks that measured the steady drip of water to keep track of hours. The Babylonians and Greeks later refined these methods, while the Romans adopted and spread the use of sundials throughout their empire.

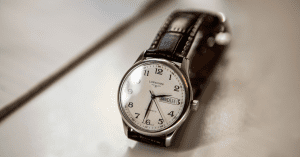

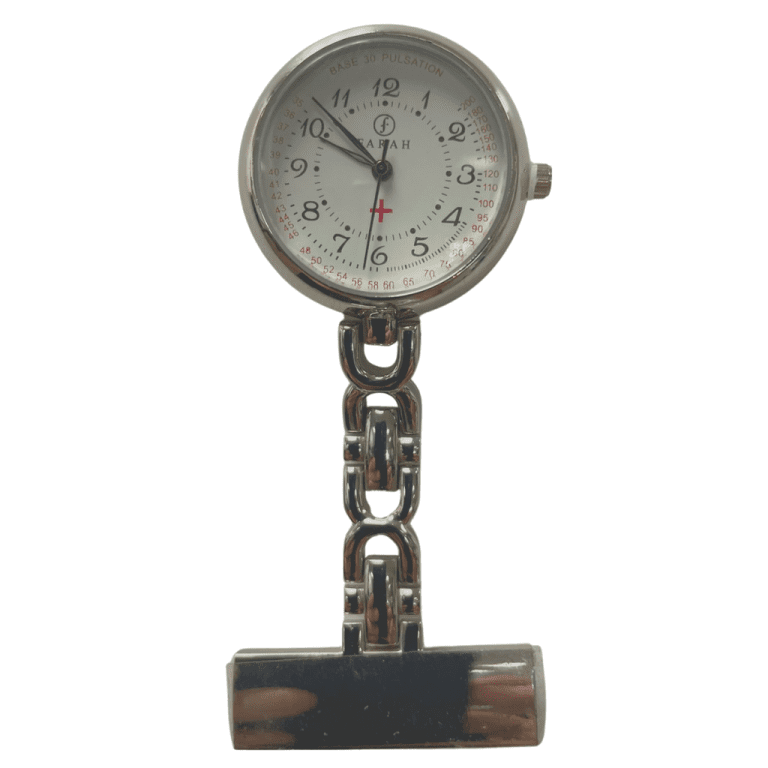

The invention of mechanical clocks in the 13th century was a turning point. For the first time, hours and minutes could be measured consistently without relying on sunlight or flowing water. These clocks were often built in church towers, ringing bells to mark the passing of time for entire towns. In the 17th century, Galileo’s studies of pendulums and Christiaan Huygens’ invention of the pendulum clock greatly improved accuracy, laying the foundation for modern timekeeping.

Today, time is measured more precisely than ever with atomic clocks, which use vibrations of atoms to keep time so exact that they lose less than a second in millions of years. This incredible accuracy is what powers GPS, global communication, and scientific discoveries.

In many ways, time is both a human creation and a natural force. We shaped it into hours, minutes, and seconds to organize our lives, but it ultimately comes from the steady rhythms of the universe itself.