On Friday, my colleague Steve Andre wrote in a staff wide email that he was considering teaching how to tell time on an analog clock to his seventh grade computer students because they can’t read the one on his wall when they sign out with a pass. On one hand, Steve was for it because analog clocks are still prevalent so it’s still a relevant life skill. But he adds that people don’t wear analog watches so much, and analog clocks’ days are numbered. He wanted our opinions on the matter.

Our opinions, and those of outside friends who have joined the discussion, crossed emotional, pedagogic, and philosophical lines. Emotionally, many were dismayed at the loss of this skill, one was even “appalled.” Many teachers were frustrated because the clocks on our classroom walls are analog, so kids need to know analog time. (I wonder why they’re not frustrated that our facilities are stuck in the 20th Century or that half of the clocks don’t work anyway.) One bridged the emotional – pedagogic divide by expressing the frustration of teaching a skill that first or second graders are not developmentally ready for.

Other pedagogic arguments included the value of using an analog clock as a concrete example of math skills. Miriam added that learning analog clocks helps visual learners:

…I believe that the analog clock can provide a vivid representation of time that digital clocks cannot. Analog clocks are great for teaching time management, concepts including the passage of time, how much time we have left to complete something, etc. Even our little kids who don’t yet have the concept of numerals can understand that “when the big hand is on this red line it’s time to line up.

Philosophically, several people compared learning analog time to learning cursive writing, another skill that’s about as common these days as an 8-track stereo. They pointed out that all anybody seems to write in cursive anymore is their signature. But isn’t that a reason to stop teaching it, rather than continue?

Barb, my favorite non-conformist, wrote a response that combines emotion, pedagogy, and philosophy:

I don’t know if it’s necessary to learn to read an analog clock; but I definitely think it is good for the brain and even better for the mind. Even though the analog clock “moves time” through a single plane or two dimensions, at least time is moving through space at some level. And time needs space although not as much as space needs time. Digital clocks offer only a linear time, and even the linearity is broken up—a kind of dotted line of time. I think our conditioned and cultural tendencies in the west—forever– and increasingly all over the planet, are already towards a mental and psychic linearity( and very much broken up at that ) which lacks depth and scope and a connection to the non-physical world. So, I love the analog clock and the sense of something moving through time and time moving through something….The only thing is that analog watches ALL lose time on my wrist pretty dramatically. But I have a great analog art clock made out of those little firecracker things that you stomp on– hanging in my kitchen. It ticks and tocks, too. I still love sensations and the tactile, visual world—so yes, analog clocks.

That makes me want to teach analog time just so I can then teach them how to find south with an analog watch.

Her comments also led to a mental digression. Our English unit of length began as the average size of sixteen residents’ feet in a given village. Daylight was divided into six equal parts so how long an hour lasted depended on the season and your latitude. So, time and distance were proportional the cycles of nature and her human inhabitants. A meter, by the way, is 1/299,792,458 of the distance light travels in a vacuum in one second. (Why not 1/300,000,000?) A second is equal to the duration of 9,192,631,770 cycles of radiation in an energy level change of the Cesium atom. (Why not 10,000,000,000?)

My own response to Steve’s original question was that I think reading analog time is about as virtuous as using a rotary phone or zip-a-grade. (I was going to use put in a picture of a zip-a-grade for younger readers, but couldn’t find a single one. There are, though, lots of zip-a-grade apps.)

Instead of comparing analog time to cursive, I compared it to reading dice, which a lot of kids can’t do anymore, either. But the digital games they play instead:

…are more cognitively demanding and require more planning, collaboration, and communications skills than board games. Plus, like any good teacher – the games they play don’t let them move on until they’ve mastered their current level while providing the motivation to continue. I’d love to be able to teach grit the way World of Warcraft does. My kids never asked me a geography or history question after playing Yahtzee or Monopoly, but they do after playing Assassin’s Creed.

To that, my colleague Cheryl fairly pointed out the advantages of dice games in developing number sense.

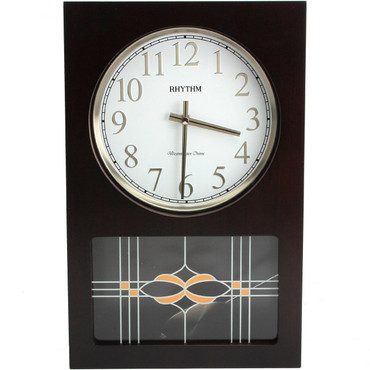

And to Steve’s earlier point about the prevalence of analog clocks in public places, I’d add that yesterday I visited the supermarket, the mall, two libraries, and a party. In those peregrinations, I saw exactly four analog clocks hanging on walls. The last was at my friend’s party in her home. Her clock was quite lovely and made me think that in terms of decorative value, analog clocks win hands down.

At the end of the day, Steve wrote to us all that he had decided to teach analog time-telling.

I’m going to pass some time watching Cesium atoms radiate.

Credited to: storiesfromschoolaz